Baraka (film)

| Baraka | |

|---|---|

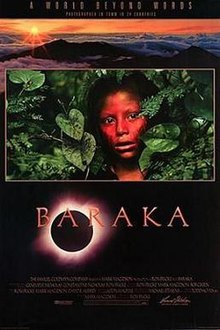

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Fricke |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Mark Magidson |

| Cinematography | Ron Fricke |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Michael Stearns |

Production company | Magidson Films |

| Distributed by | The Samuel Goldwyn Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | None |

| Budget | $2 million |

| Box office | $1.3 million[1] |

Baraka is a 1992 American non-narrative documentary film directed by Ron Fricke. The film is often compared to Koyaanisqatsi, the first of the Qatsi films by Godfrey Reggio for which Fricke served as cinematographer.[2] It was photographed in the 70 mm Todd-AO format, and is the first film ever to be restored and scanned at 8K resolution.[3][4]

Content

[edit]Baraka is a documentary film with no narrative or voice-over. It explores themes via a compilation of natural events, life, human activities and technological phenomena shot in 24 countries on six continents over a 14-month period.

The film is named after the Islamic concept of baraka, meaning blessing, essence or breath.[5][4]

The film is Ron Fricke's follow-up to Godfrey Reggio's similar non-verbal documentary film Koyaanisqatsi. Fricke was cinematographer and collaborator on Reggio's film, and for Baraka he struck out on his own to polish and expand the photographic techniques used on Koyaanisqatsi. Shot in 70 mm, it includes a mixture of photographic styles including slow motion and time-lapse. Two camera systems were used to achieve this. A Todd-AO system was used to shoot conventional frame rates, but to execute the film's time-lapse sequences Fricke had a special camera built that combined time-lapse photography with perfectly controlled movements.[6]

Locations featured include the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the Ryōan temple in Kyoto, Lake Natron in Tanzania, burning oil fields in Kuwait, the smouldering precipice of an active volcano, a busy subway terminal, the aircraft boneyard of Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, tribal celebrations of the Maasai in Kenya, and chanting monks in the Dip Tse Chok Ling monastery.

The film features a number of long tracking shots through various settings, including Auschwitz and Tuol Sleng, over photos of the people involved, past skulls stacked in a room, to a spread of bones. It suggests a universal cultural perspective: a shot of an elaborate tattoo on a bathing Japanese yakuza precedes a view of tribal paint.

Reissue

[edit]Following previous DVD releases, in 2007 the original 65 mm negative was rescanned at 8K resolution with equipment designed specifically for Baraka at FotoKem Laboratories. The automated 8K film scanner, operating continuously, took more than three weeks to finish scanning more than 150,000 frames (taking approximately twelve to thirteen seconds to scan each frame), producing over thirty terabytes of image data in total.

After a 16-month digital intermediate process, including a 96 kHz/24-bit audio remaster by Stearns for the DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack, the result was re-released on DVD and Blu-ray in October 2008. At the time, project supervisor Andrew Oran described the reissue of Baraka as "arguably the highest-quality DVD that's ever been made".[7] Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert described the Blu-ray release as "the finest video disc I have ever viewed or ever imagined."[4]

Sequel

[edit]A sequel to Baraka, Samsara, also shot in 70 mm and made by the same filmmakers, premiered at the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival and was released internationally in August 2012.[8][9][10]

Reception

[edit]Baraka holds a score of 81% on Rotten Tomatoes out of twenty-six reviews.[2] Roger Ebert included the film in his "Great Movies" list, writing: "If man sends another Voyager to the distant stars and it can carry only one film on board, that film might be Baraka."[4]

Production

[edit]Music

[edit]The score is by Michael Stearns and features music by, among others, Dead Can Dance, L. Subramaniam, Ciro Hurtado, Inkuyo, Brother, Anugama & Sebastiano and David Hykes.

In 2019, German composer Mathias Rehfeldt released the concept album Baraka, inspired by the film.[11]

Filming

[edit]The project was shot in 152 locations in 24 countries.[12]

Africa

[edit]- Egypt: Cairo; City of the Dead; Giza pyramid complex; Karnak temple, Luxor; Ramesseum

- Kenya: Lake Magadi; Mara Kichwan Tembo Manyatta; Mara Rianta Manyatta; Maasai Mara

- Tanzania: Lake Natron

United States

[edit]- Arizona: American Express, Phoenix; Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Chinle; Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, Tucson; Peabody coal mine, Black Mesa; Phoenix

- California: Big Sur; Los Angeles; Santa Cruz (chicken farm scenes)[13]

- Colorado: Mesa Verde National Park

- Hawaii: Haleakalā National Park, Maui; Kona; Puʻu ʻŌʻō, Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park

- New York: Empire State Building, Manhattan, New York City; Grand Central Terminal, Manhattan, New York City; Helmsley Building, Manhattan, New York City; McGraw-Hill Building, Manhattan, New York City; World Trade Center, Manhattan, New York City; Green Haven Correctional Facility, Beekman, New York; Stormville, New York

- Utah: Arches National Park, Moab; Canyonlands National Park, Moab

- Others: Shiprock, New Mexico; White House, Washington, D.C.

South America

[edit]- Argentina: Iguazu Falls, Misiones

- Brazil: Carajás Animal Reserve, Pará; Iguazu Falls, Paraná; Ipanema, Favela da Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro; Caiapó Village, Pará; Porto Velho, Rondônia; Represa Samuel, Rondônia; Rio Preto, Minas Gerais; São Paulo City, São Paulo state

- Ecuador: Barrio Mapasingue, Guayaquil; Cementerio Ciudad Blanca;[14] Galápagos Islands; Guayaquil

Asia

[edit]- Cambodia: Angkor Thom; Angkor Wat; Angkor; Bayon; Phnom Penh; Preah Khan; Siem Reap; Ta Prohm; Tonle Omm Gate; Tuol Sleng Museum; Sonsam Kosal Killing Fields

- China: Beijing; Great Hall of the People; Tiananmen Square; Guilin; Li River, Qin Shi Huang; Xi'an

- Hong Kong: Kowloon Walled City, Kowloon

- India: Calcutta, West Bengal; Chennai, Tamil Nadu; Ganges River; Ghats; Kailashnath Temple, Varanasi; National Museum of India, New Delhi; Varadharaja Temple, Varanasi

- Indonesia: Borobudur; Java; Candi Nandi; Candi Prambanan; Gudang Garam cigarette factory; Kasunanan Palace; Surakarta; Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta; Kediri; Tabanan; Bali; Mancan Padi; Mount Bromo Valley; Tampak Siring; Tegallalang; Gunung Kawi temple; Uluwatu

- Iran: Imam Mosque; Imam Reza Shrine, Mashhad; Isfahan; Persepolis; Shah Chiragh; Shiraz

- Japan: Green Plaza Capsule Hotel; Hokke-Ji temple; JVC Yokosuka Factory; Kyoto; Meiji Shrine; Nagano Springs; Nara; Nittaku; Ryōan-ji temple; Sangho-ji Temple; Shinjuku Station; Tokyo; the Hachikō Exit, Shibuya Station; Tomoe Shizung & Hakutobo; Yamanouchi, Nagano; Zōjō-ji temple

- Israel: Church of the Holy Sepulchre; Western Wall

- Kuwait: Ahmadi; Burgan Field; Jahra Road, Mitla Ridge (Farouk Abdul-Aziz researched and produced this segment)

- Nepal: Bhaktapur; Boudhanath; Durbar Square, Kathmandu; Hanuman Ghat; Himalayas; Mount Everest; Mount Thamserku; Pasupati; Swayambhu

- Saudi Arabia: Mecca

- Thailand: Ayutthaya Province; Bang Pa-In; Bangkok; NMB Factory; Patpong; Soi Cowboy; Wat Arun; Wat Suthat

- Turkey: Galata Mevlevi temple

Oceania

[edit]- Australia: Bathurst Island; Cocinda; Jim Jim Falls; Kakadu National Park; Kunwarde Hwarde Valley; Uluru

Europe

[edit]- Poland: Oświęcim (German Auschwitz concentration camp); Sztutowo (German Stutthof concentration camp); Bytom

- France: Chartres Cathedral; Notre-Dame de Reims

- Vatican City: St. Peter's Basilica

- Turkey: Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Baraka (1993)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Baraka". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ "Baraka". Spirit of Baraka. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, Roger (16 October 2008). "Great Movies: Baraka (1992)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (27 October 1993). "'Baraka'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "A Conversation with Mark Magidson and Ron Fricke". IN70MM.com. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Oran, Andrew (2008). Baraka: "Restoration" feature documentary (DVD/Blu-ray). Magidson Films, Inc.

- ^ "About Samsara". BarakaSamsara.com. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Toronto film festival 2011: the full programme". The Guardian. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Johnston, Trevor (28 August 2012). "Samsara". Time Out Worldwide. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Baraka". CD Baby. Retrieved 2 December 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Baraka Filming Locations". BarakaSamsara.com. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Chicken factory farm, Santa Cruz, CA". BarakaSamsara.com. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "La Ciudad Blanca (The White City) Cemetery, Guayaquil, Ecuador". Spirit of Baraka. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Baraka at IMDb

- Baraka at Spirit of Baraka

- 1992 films

- 1992 documentary films

- 1992 in the environment

- American documentary films

- Documentary films about spirituality

- Environmental films

- Films directed by Ron Fricke

- Films scored by Michael Stearns

- Films shot in Argentina

- Films shot in Australia

- Films shot in Brazil

- Films shot in China

- Films shot in Ecuador

- Films shot in Egypt

- Films shot in Hong Kong

- Films shot in India

- Films shot in Indonesia

- Films shot in Iran

- Films shot in Israel

- Films shot in Japan

- Films shot in Kenya

- Films shot in Kuwait

- Films shot in Nepal

- Films shot in Poland

- Films shot in Reims

- Films shot in Saudi Arabia

- Films shot in Tanzania

- Films shot in Thailand

- Films shot in Turkey

- Films without speech

- Non-narrative films

- The Samuel Goldwyn Company films

- Films shot in Bhaktapur

- Films shot in Kolkata

- Films shot in Chennai

- Films shot in Varanasi

- Films shot in Delhi

- Documentary films about India

- 1990s American films

- Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- Giza pyramid complex

- Uluru

- Films shot in Angkor Wat